I’ve been reluctant to comment on the latest fad in our industry, generative AI, simply because everybody has weighed in on it. I do also try to avoid commenting on subjects outside of my scope of authority. Increasingly, though, people are coming to me at work and asking how we can incorporate this technology into our products, how our competitors are doing it, and what our AI strategy is. So I guess I am an authority.

To be honest, I didn’t play with ChatGPT until this week. When I first looked at it, it wanted my email address and phone number and I wasn’t sure I wanted to provide that to our new AI overlords. So I passed on it. Then Cisco release an internal-only version, which is supposedly anonymous, so I decided to try it out.

My first impression was, as they say, “meh.” Obviously its ability to interpret and generate natural language are amazing. Having it recite details of its data set in the style of Faulkner was cool. But overall, the responses seemed like warmed-over search-engine results. I asked it if AI is environmentally irresponsible since it will require so much computing power. The response was middle-of-the-road, “no, AI is not environmentally irresponsible” but “we need to do more to protect the environment.” Blah, blah. Non-committal, playing both sides of the coin. Like almost all of its answers.

Then I decided to dive a bit deeper into a subject I know well: Ancient Greek. How accurately would ChatGPT be on a relatively obscure subject (and yet one with thousands of years of data!)

Even if you have no interest, bear with me. I asked ChatGPT if it knew the difference between the Ionic dialect of Herodotus and the more common dialect of classical Athens. (Our version, at least, does not allow proper names so I had to refer to Herodotus somewhat elliptically.) It assured me it did. I asked it to write “the men are arriving at Athens” in the dialect of Herodotus. It wrote, “Ἀφίκοντο οἱ ἄνδρες εἰς Ἀθήνας,” which is obviously wrong. The first word there, “aphikonto“, would actually be “apikonto” in the dialect of Herodotus. He was well known for dropping aspirations. The version ChatGPT gave me would be the classical Attic version.

I let ChatGPT know it was wrong, and it dutifully apologized. Then I asked it to summarize the differences in the dialects. It said to me:

Herodotus and Ionic writers typically removed initial aspirations, while the Attic dialect retained them. For example, “Ἀφίκοντο” (Herodotus) vs. “ἔφικοντο” (Attic)

Uh, you don’t need to know the Greek alphabet to see it made exactly the same mistake, again. It should have said that Herodotus would use “Ἀπίκοντο” (apikonto) whereas in Attic the word would be “Ἀφίκοντο” (aphikonto.)

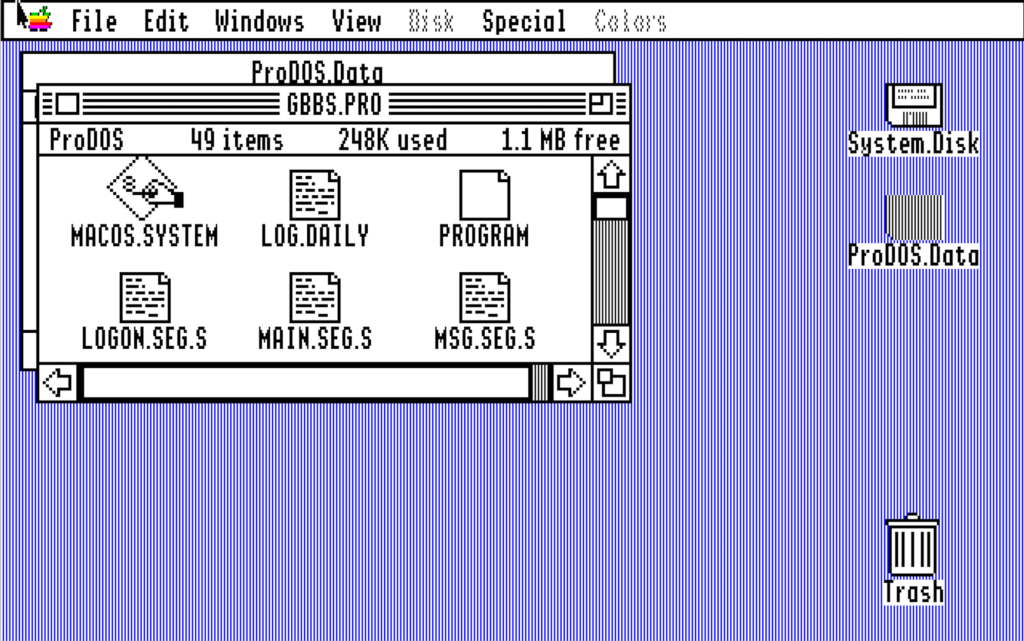

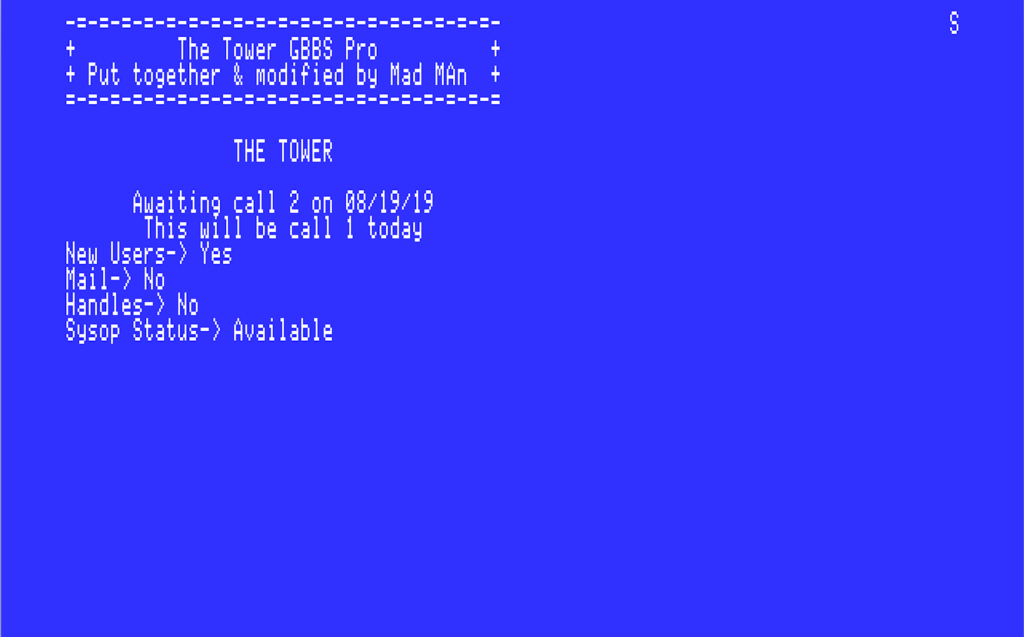

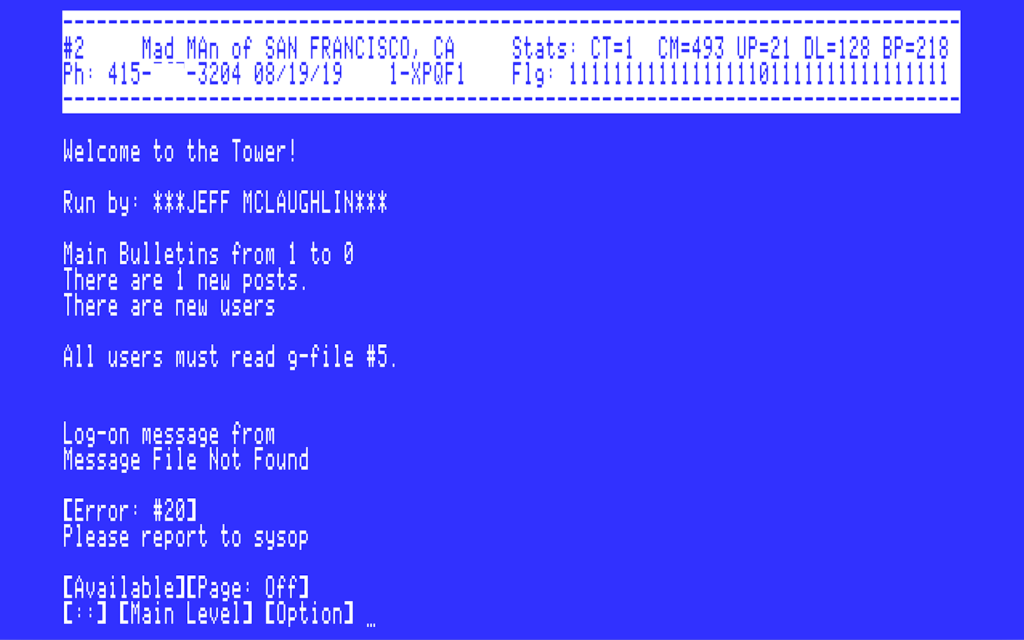

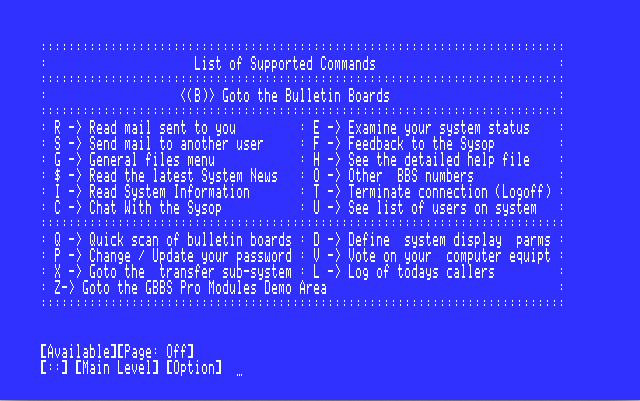

Here’s a little more computer-person-friendly example. I decided to ask about my other favorite subject, retro computing. I asked, “What is the difference between the Apple IIGS ProDOS 8, ProDOS 16, and GS/OS operating systems?” Among other things, ChatGPT responded that GS/OS ” introduced features such as a desktop metaphor, drop-down menus, and a hierarchical file system.” Which happens to be wrong. ProDOS 16 actually introduced those features. (In fact, ProDOS 8 introduced the hierarchy.) I pointed this out. “You are correct, and I apologize for the oversight in my previous response. I misspoke in stating that GS/OS introduced [those] features.” Hmmm.

I’m testing it and I know the right answers. The problem would arise if I were trusting ChatGPT to provide me with a correct answer. There have been plenty of examples of mistakes made by ChatGPT, such as adding a “permit any” to the top of access-lists.

The issue is, ChatGPT sounds authoritative when it responds. Because it is a computer and speaking in natural language, we have a tendency to trust it. And yet it has consistently proven it can be quite wrong on even simple subjects. In fact, our own version has the caveat “Cisco Enterprise Chat AI may produce inaccurate information about people, places, or facts” at the bottom of the page, and I’m sure most implementations of ChatGPT carry a similar warning.

Search engines place the burden of determining truth or fiction upon the user. I get hundreds or thousands of results, and I have to decide which is credible based on the authority of the source, how convincing it sounds, etc. AI provides one answer. It has done the work for you. Sure, you can probe further, but it many cases you won’t even know the answer served back is not trustworthy. For that reason, I see AI tools to be potentially very misleading and potentially harmful in some circumstances.

That aside, I do like the fact I can dialog with it in ancient Latin and Greek, even if it makes mistakes. It’s a good way to kill time in boring meetings.